Seeds of Deception: How the Victory Garden Campaign Romanticized Farming and Sowed the Roots of Policy Failure

What began as a wartime food security campaign, in hindsight, it was a well-dressed propaganda push with long-term consequences for environmental policy and agricultural understanding.

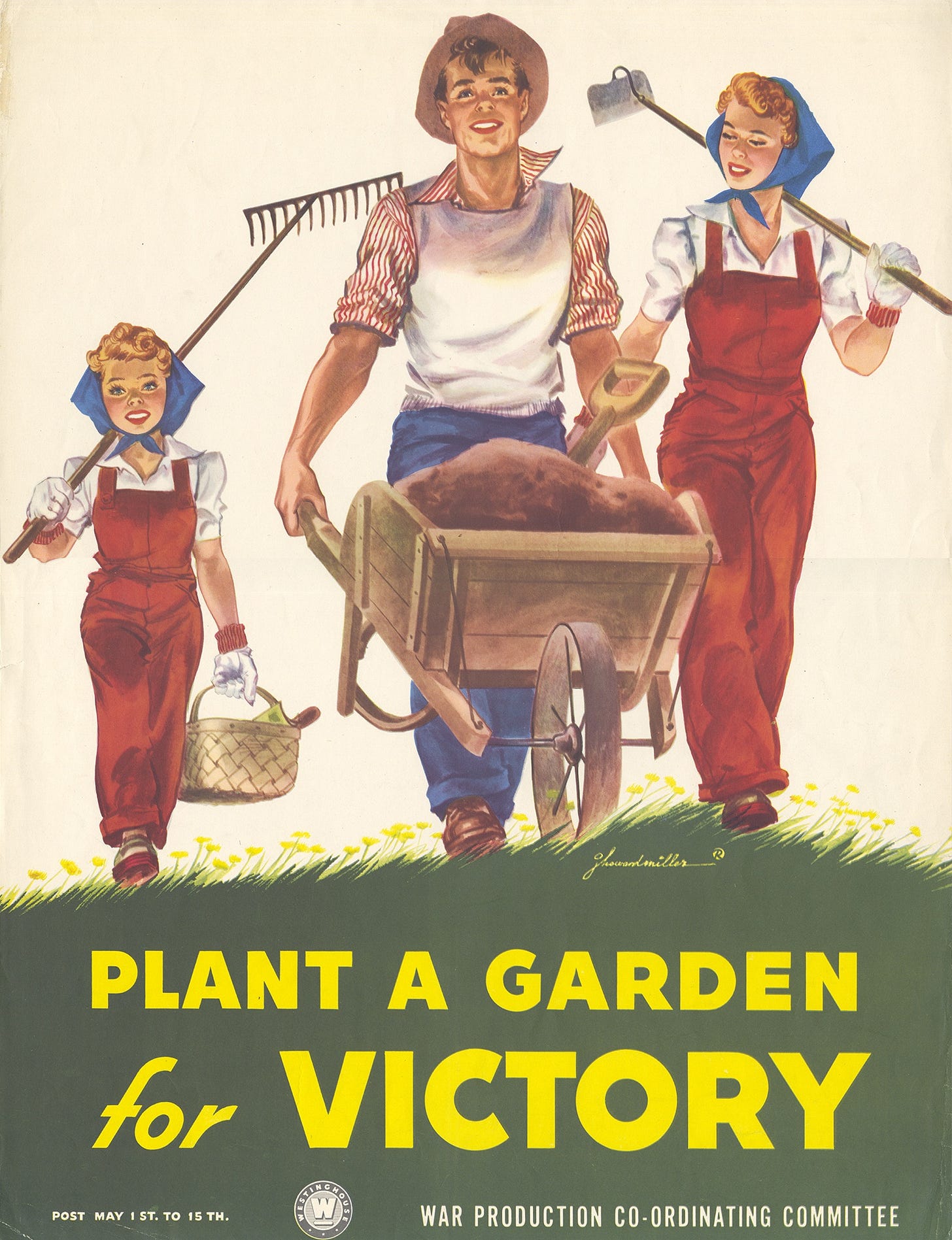

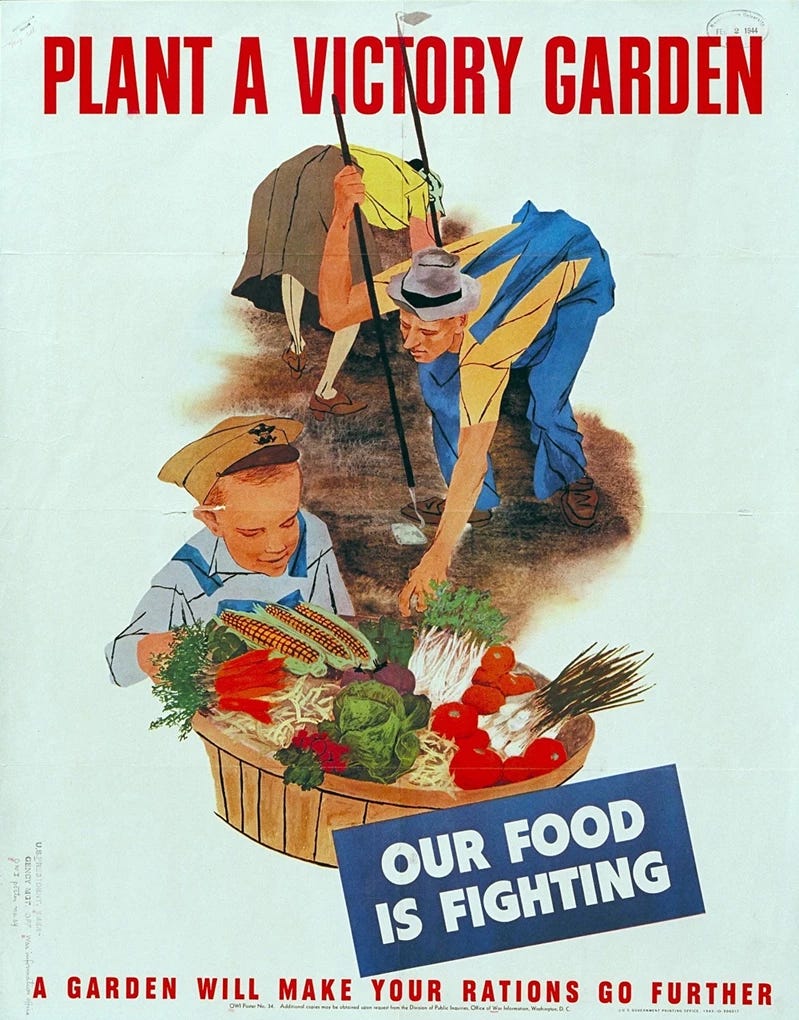

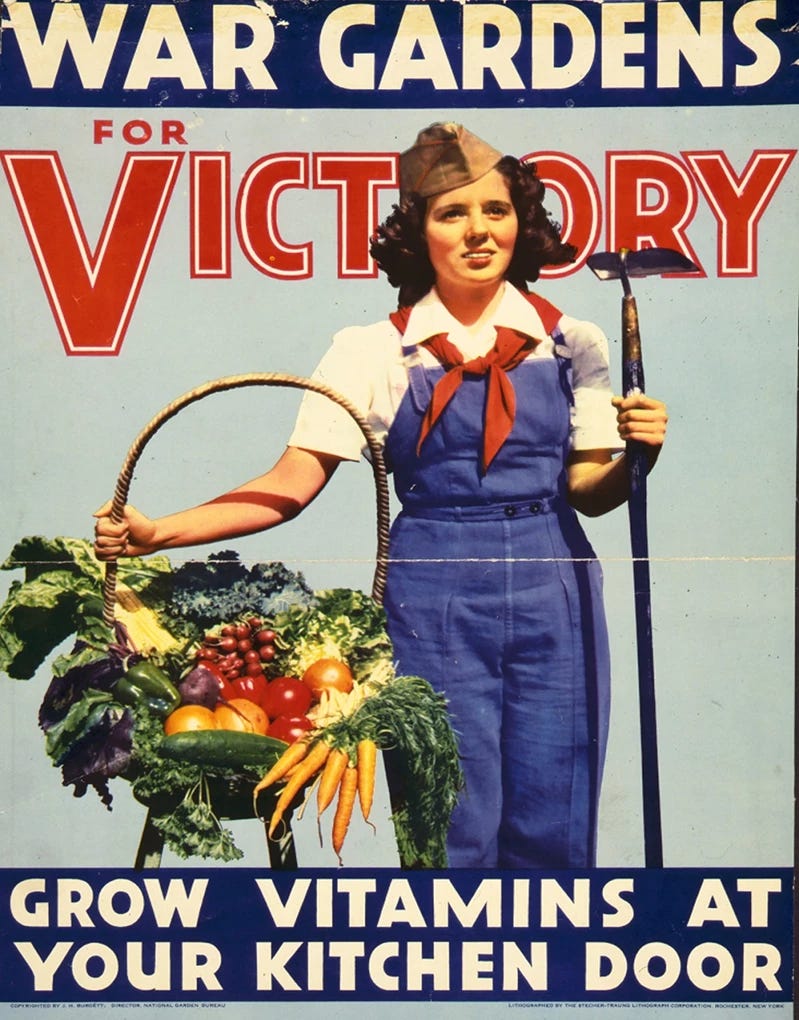

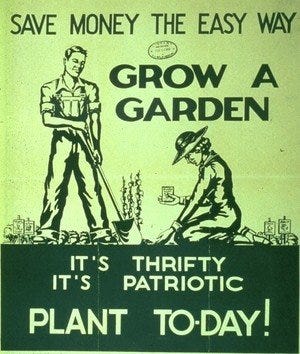

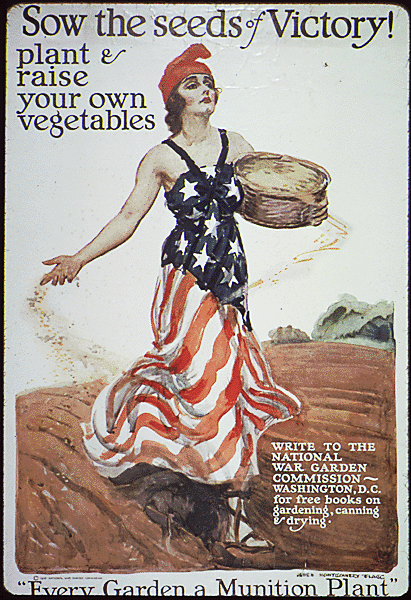

It started with a poster.

A clenched fist gripped a garden hoe, bold letters declared: “Sow the Seeds of Victory!” Across the American landscape—on walls, billboards, pamphlets, and cereal boxes—Uncle Sam wasn't just asking you to buy war bonds. He was telling you to dig.

By 1943, nearly 20 million Americans had turned their backyards, school yards, and vacant city lots into “Victory Gardens.” These weren’t mere symbols. They were heralded as patriotic acts, parallel to wielding a rifle on the frontlines or riveting steel on the home front.

But what began as a wartime food security campaign would, in hindsight, be a well-dressed propaganda push with long-term consequences for environmental policy, agricultural understanding, and even the American tax code. What the U.S. government branded as grassroots resilience was, in part, a manicured campaign of romantic idealism that would paper over deeper soil degradation, regulatory negligence, and an emerging grift culture tying patriotism to ag policy.

Chapter 2: The Narrative Takes Root

In private meetings at the Department of Agriculture in early 1942, Secretary Claude Wickard sat with a team of propagandists, agronomists, and Roosevelt's inner circle. According to archived memos and interview notes, Wickard saw opportunity.

“There is no better time,” he said in a January 12 briefing, “to teach Americans to rely on themselves—even if we quietly orchestrate the entire thing.”

Roosevelt, who once famously turned a White House lawn into a demonstration garden during World War I, gave his approval. But this time the strategy would be more coordinated—and more cinematic.

With Hollywood stars endorsing the campaign and Madison Avenue’s best minds contributing slogan work, the Victory Garden movement didn’t just spread—it exploded. Local mayors were enlisted. Agricultural Extension offices distributed soil tips and pamphlets, many of them simplified to the point of scientific error.

“They dumbed it down,” said Dr. Ellen Marshall, an agricultural historian at Cornell. “Compost was reduced to garbage in a pit. Soil pH was never explained. It became folk magic, not farming science.”

Even worse, Marshall argues, “They made the soil an afterthought.”

Chapter 3: A Harvest of Misinformation

Despite its popularity, internal USDA reports from 1944 and 1945 show troubling data: many gardens failed. The government didn’t publicize it.

A 1945 internal audit from the Office of War Information, never released to the press, found that nearly 40% of urban Victory Gardens yielded less than 10 pounds of produce. Many failed due to poor soil quality, lack of access to compost, or simply planting in shaded lots.

Rather than teach regenerative practices or long-term soil management, the campaign stayed focused on short-term production and morale. The deeper problem—how Americans conceptualized agriculture—was being distorted.

“Victory Gardens suggested anyone could farm,” said Robert Lytle, a former soil conservationist with the USDA, “as long as you were patriotic enough. But good farming isn’t patriotic. It’s scientific. It’s complex. It takes decades of understanding ecosystems.”

Chapter 4: From Victory to Vacuum

After the war, the gardens were quietly abandoned. There was no endgame for them—no policy for urban farming, no tax incentive to keep soil healthy, no continuity program. What lingered, however, was the myth.

President Truman briefly considered integrating small-scale agriculture into housing policy in 1947, but lobbyists from the fertilizer and pesticide industries argued for a different vision. One memo from the American Chemical Association called small-scale gardening “a quaint relic” and pushed instead for “modern, efficient agriculture using emerging technologies.”

What replaced the Victory Garden was a shift in federal ag policy—one increasingly tied to synthetic fertilizers, monoculture, and large-scale industrial production. But the romanticism lingered in public memory.

“This was the con,” said a former House Agriculture staffer who requested anonymity. “Victory Gardens made Americans think they understood the land. So they didn’t ask questions when policymakers paved it over.”

Chapter 5: Enter the Grifters

As farming industrialized, a new class of lobbyists emerged—many of them former Victory Garden campaigners, now on the payroll of chemical companies and land developers.

They carried with them a script: the land is plentiful, farming is simple, and technology can solve any shortage.

Congress bought it.

Between 1950 and 1970, federal subsidies shifted dramatically toward industrial agriculture. Policies like PL 480 and farm bills crafted under the guise of “food for peace” prioritized commodity crops. Little attention was given to the soil quality or environmental impact.

“You could trace some of this back to the Victory Garden era,” said Sarah Koenig, an environmental economist. “The idea that farming could be manipulated for patriotic or economic goals—with no regard for ecology—was normalized.”

One consequence: soil degradation across the Midwest. According to a 1972 USDA report, 75% of cropland in Iowa showed signs of serious nutrient depletion. The agency attributed this in part to chemical dependency, monocropping, and erosion from poor land management.

Chapter 6: Tax Codes and Tilled Earth

By the 1980s, the American farmer was no longer the backyard gardener. He was a tax vehicle.

Large corporations bought swaths of farmland for depreciation write-offs, while developers used “ag use” designations to dodge property taxes. Small-scale, sustainable farmers had no seat at the table.

“The very people the Victory Garden was supposed to inspire were abandoned,” said Mark Withers, a North Dakota soil advocate. “Meanwhile, the idea of gardening remained a political prop.”

Victory Gardens were invoked during the 1976 Bicentennial and again during the 2008 financial collapse. Michelle Obama even planted one at the White House in 2009, though her initiative ran into lobbying resistance from Big Ag groups concerned about its message.

Ironically, the same government that once told Americans to grow their own food now subsidized corn syrup, restricted urban composting in several states, and allowed agribusinesses to dominate food systems—under the same flag of “feeding the nation.”

Chapter 7: The Environmental Bill Comes Due

Today, the United States faces widespread soil loss, water contamination from nitrates, and environmental degradation tied to poor agricultural practices. Climate change, coupled with decades of topsoil mismanagement, has exacerbated the crisis.

A 2022 EPA study concluded that soil erosion costs the U.S. economy more than $44 billion annually in lost productivity and ecosystem repair. Yet, few in Congress draw a straight line from wartime propaganda to current policy.

In private, however, the awareness exists. In a leaked 2019 strategy memo from a major ag lobbying firm, one executive warned: “There is growing skepticism about industrial ag. We must reframe the Victory Garden legacy as intentional and environmentally sound, regardless of its flaws.”

In other words: rewrite history.

Chapter 8: Digging Ourselves Out

There is a new generation trying to undo the damage. Organizations like Kiss the Ground and the Rodale Institute advocate for regenerative farming, soil health, and compost science. Some are even trying to reclaim the Victory Garden brand—minus the propaganda.

Urban farming co-ops in Detroit, community composting in San Francisco, and regenerative ranchers in Montana are planting a new kind of patriotism—one rooted in science and sustainability, not slogans.

But the federal policy lag remains.

Tax codes still reward depletion over regeneration. Lobbyists still choke out small producers. And Americans, conditioned by a campaign from 80 years ago, still see the soil as something we can simply dig into—without consequence.

Epilogue: The Dirt Tells the Truth

The posters were beautiful. The message was stirring. But the movement was manipulated.

Victory Gardens offered the illusion of self-reliance, while setting the stage for an agricultural model that would centralize power, degrade the environment, and privilege corporate interests over ecological literacy.

In the words of one aging USDA official, reflecting in a 1990 oral history: “We told people to garden for victory. We never told them how to care for the land after the war.”

The seeds of misinformation were sown. And today, we are still reaping the costs.

Wade McBride is a seasoned agricultural economist, columnist, and rural markets strategist known for his unfiltered insights into the intersection of American farming, commodity markets, and government policy.